Portfolio 5 IA

Quantifying uncertainties and Bayesian networks, Probabilistic reasoning over time and Kalman filters

Introduction

In the complex and dynamic world of data analysis and system modeling, understanding and managing uncertainty is a central challenge. Various methodologies and models have been developed to quantify and navigate these uncertainties, each suited to different scenarios and requirements. This introduction will briefly overview key concepts and tools widely used in this domain, focusing on their applications and underlying principles.

We begin with statistical inference, a fundamental approach in statistics for making predictions or drawing conclusions about a population based on sample data. It encompasses descriptive and inductive inference, crucial for understanding data and making broader generalizations.

Moving to the realm of temporal modeling, we encounter Markov Models and Kalman Filters. Markov Models, including Hidden Markov Models (HMMs), are powerful in handling temporal data and uncertainties, offering insights into dynamic systems. Kalman Filters are particularly effective for continuous data tracking and prediction, merging predictions with noisy observational data to estimate the true state of a system accurately.

In the field of artificial intelligence, Bayesian Networks serve as a versatile tool for modeling complex relationships between variables under uncertainty. These directed acyclic graphs encapsulate conditional dependencies and are instrumental in areas ranging from medical diagnostics to machine learning.

On the more technical side, we delve into the mechanics of probabilistic models, discussing the nuances of transition and sensor models within systems like robotic navigation. These models describe how a system’s state changes over time and the likelihood of various observations for different states, respectively.

Furthermore, we explore probabilistic reasoning over time, emphasizing how methods like Hidden Markov Models and Kalman Filters adapt probabilistic reasoning to temporal and dynamic contexts. These approaches are crucial for applications where both time and uncertainty play significant roles, such as in GPS tracking or financial time series analysis.

Overall, this introduction sets the stage for a deeper exploration of each of these methodologies, highlighting their significance in managing uncertainty and extracting meaningful insights from complex data.

Uncertainties

Navigating the realm of uncertainties is a pivotal aspect in artificial intelligence (AI), where data often presents itself as fragmented, ambiguous, or subject to fluctuation. Several strategies have been developed to address these challenges, each offering unique perspectives and solutions:

Probabilistic Modeling: This strategy employs probabilistic methods such as probability theory and statistics to manage and represent uncertainties in data. Bayesian Networks, in particular, are a formidable tool in this domain, offering the capability to model probabilities and dynamically update them in light of new data.

Fuzzy Logic: In situations where binary true/false does not suffice, fuzzy logic provides a nuanced approach to handle uncertainty. It operates on the principle of degrees of truth, ranging between 0 and 1, allowing for a more flexible representation of reality.

Robust Machine Learning: Developing machine learning algorithms that can withstand data inconsistencies and variations is vital. Such robust algorithms ensure that AI models maintain their effectiveness and accuracy in diverse and unpredictable environments.

Rule-Based Systems: These systems rely on explicit rule-based frameworks to make decisions, particularly useful when dealing with incomplete or ambiguous data. They offer a structured approach to decision-making, grounded in predefined logic.

Monte Carlo Sampling: This statistical technique is instrumental in evaluating and propagating uncertainties in complex models. By generating random samples, Monte Carlo sampling provides a way to approximate probability distributions and assess various outcomes.

Adaptive Systems with Continuous Feedback: Creating systems that adapt in real-time as new data emerges is critical for handling uncertainties. Continuous feedback mechanisms enable these systems to evolve and adjust their models to better suit changing conditions.

Meta-Learning: This innovative approach allows AI models to learn how to learn, making them more adept at handling uncertain and evolving scenarios. Meta-learning is particularly useful in situations where data distributions are not static and change over time.

Multi-Source Data Integration: Combining data from diverse sources can be a powerful way to reduce uncertainties. By leveraging different perspectives and types of information, AI systems can achieve a more comprehensive and reliable understanding of complex situations.

Transparency and Explainability in AI: Ensuring that AI models are transparent and their decisions explainable is crucial. This helps users understand and trust the decision-making process, especially in scenarios where uncertainty is a significant factor.

Hybrid Methodologies: Integrating various techniques and methods to form hybrid systems offers a robust way to tackle uncertainty. These systems can leverage the strengths of different approaches to better handle complex and uncertain environments.

In the wider context of uncertainty, three interconnected concepts are vital: systemic complexity, rhetorical ignorance, and practical ignorance.

Systemic Complexity: This term refers to the intricate and often intertwined nature of real-world systems, characterized by numerous variables, nonlinear interactions, and emergent behaviors. Such complexity can significantly amplify uncertainty, making it challenging to fully predict or understand these systems.

Rhetorical Ignorance: It involves acknowledging the inherent limits of our knowledge in certain areas. This awareness that not everything can be known or predicted underscores the importance of honesty about the extent of our understanding, especially in complex and uncertain scenarios.

Practical Ignorance: This concept deals with the uncertainty in actionable knowledge – knowing what to do when faced with uncertainty. It’s about the challenges in decision-making and strategy formulation when the path forward is not clear, necessitating ongoing adaptation and learning.

Utility

The concept of utility in economics and decision-making theories is an essential framework to comprehend how individuals make choices, especially under uncertain circumstances. This concept, enriched by the contributions of numerous economists, addresses how people assess and decide between different options. Here are the fundamental elements of utility theory:

Nature of Utility: Utility represents an individual’s level of satisfaction or pleasure derived from consuming goods or services. This measure is inherently subjective, differing from one person to another based on personal preferences and perceptions.

Marginal Utility Concept: The notion of marginal utility deals with the additional satisfaction gained from consuming an extra unit of a good or service. This idea is intrinsically linked to the concept of diminishing returns, suggesting that the added utility decreases as one continues to consume more of the same good.

Indifference Curves Analysis: Utility is often visualized using indifference curves. These graphical representations illustrate various combinations of goods or services that yield equivalent satisfaction levels for a consumer, highlighting their preferences and the choices they are indifferent to.

Utility in Uncertain Conditions: In scenarios where outcomes are uncertain, utility theory evolves to include the idea of expected utility. This involves assessing the potential satisfaction from different outcomes, weighted by their respective probabilities of occurring.

Expected Utility Theory: Expanding utility theory into realms of uncertainty, the expected utility theory posits that individuals make decisions based on the anticipated satisfaction from various possible outcomes, considering both the nature of these outcomes and their likelihood.

Decision-Making Rationality: Within utility theory, it’s assumed that individuals act rationally, striving to maximize their satisfaction or utility, while being constrained by their resources and the limitations of their environment.

Understanding Diminishing Marginal Utility: The principle of diminishing marginal utility suggests a decrease in added satisfaction with increased consumption of a particular good. However, this does not necessarily imply a reduced overall desire for consumption, highlighting a nuanced aspect of consumer behavior known as the paradox of diminishing marginal utility.

Decision theory

- Preferences, expressed through utilities, are combined with probabilities to form the foundation of decision theory. This is encapsulated in the equation:

1

Decision theory = probability theory + utility theory

The fundamental idea of decision theory is that a rational agent is one who chooses an action that yields the highest expected utility, which is calculated by the average of all possible outcomes of the action.

This is referred to as the principle of maximum expected utility, abbreviated as MEU (from the English “maximum expected utility”).

In essence, decision theory integrates concepts from both probability and utility theories to explain and predict the decision-making behavior of rational agents under conditions of uncertainty. The MEU principle is a cornerstone of this theory, suggesting that rational decisions are made by weighing the potential outcomes by their associated utilities and the probabilities of these outcomes occurring.

Basic probability notations

In the field of probability theory, basic notations are essential tools for expressing and quantifying the uncertainty of various events. Let’s explore some of these fundamental notations with a twist, presenting them in a way that parallels yet differs from the original description:

Sample Space (S): The sample space is the complete set of all conceivable outcomes of a random experiment. This universal set, designated by S, encompasses every individual outcome that could possibly manifest.

Event (E): An event represents a specific collection of outcomes within the sample space S, essentially a particular subset of S. It’s typically symbolized by E.

Probability of an Event (P(E)): The probability of an event, indicated as P(E), is a numerical value indicating the likelihood of the occurrence of E. Probabilities are scaled between 0 and 1, where a probability of 0 means the event cannot occur, and 1 indicates certainty of occurrence.

Event Complement (E∁): The complement of an event E, noted as E∁, includes all possible outcomes not in E. The probability of the event’s complement is calculated by P(E∁)=1−P(E).

Union of Events (E∪F): The union of two events, E and F, denoted E∪F, encompasses all outcomes that are part of E or F or both.

Intersection of Events (E∩F): The intersection of events E and F, indicated by E∩F, includes all outcomes that E and F have in common.

Conditional Probability (P(E∣F)): The conditional probability, P(E∣F), denotes the likelihood of event E happening given that event F has occurred. It is determined by the formula P(E∣F)=P(E∩F) / P(F).

Independence of Events: Events E and F are considered independent if the occurrence of one does not influence the likelihood of the other occurring. This is signified by E⊥F, with the mathematical definition being P(E∩F)=P(E)⋅P(F) when events are truly independent.

Law of Total Probability: This theorem connects the probability of an event E to its conditional probabilities across a collection of mutually exclusive and exhaustive events B1, B2, …, Bn. It’s expressed as P(E)=∑ P(E∣Bi)⋅P(Bi) across all i.

Independence

These notations and concepts form the backbone for understanding and working with probabilities in a wide array of fields, from statistics to information theory and artificial intelligence. They offer a precise language for articulating and computing the probabilistic relationships between events.

In the realm of probability, the concept of independence between two events is fundamental. Events A and B are deemed independent if the occurrence or non-occurrence of one does not change the likelihood of the other occurring. This relationship is expressed mathematically by the equation P(A∩B) = P(A)⋅P(B), meaning the probability of both events happening simultaneously is the product of their individual probabilities.

Independence also implies that the non-occurrence of A (denoted as A’s complement, ∁A) maintains its non-effect on the probability of B, and vice versa. However, it’s crucial to understand that independent events are not necessarily mutually exclusive—they can occur together.

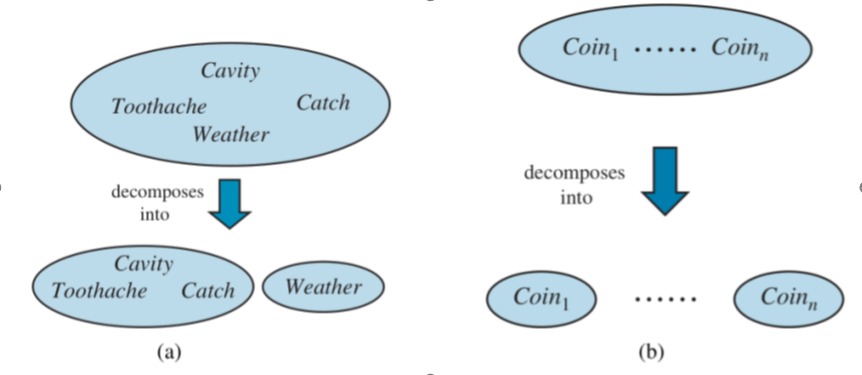

Conditional independence takes this a step further. It describes a situation where two events, A and B, are independent of each other, given the occurrence of a third event, C. Mathematically, this is represented as P(A∩B∣C) = P(A∣C)⋅P(B∣C), indicating that the influence of C renders A and B independent.

To confirm conditional independence, one must check if the ratio of the joint probability to the product of the conditional probabilities equals one. If this condition is met, A and B are conditionally independent given C.

Understanding independence and conditional independence is crucial for statistical modeling and interpreting relationships between events. These concepts allow us to analyze complex systems and the probabilistic interdependencies within.

Bayes’ Rule

Bayes’ Theorem is an essential mechanism in the world of probability and statistics, serving as a means to revise our beliefs in light of new evidence. In essence, it provides a way to calculate the probability of a hypothesis A, given the occurrence of an event B. The theorem’s equation is:

| [ P(A | B) = \frac{P(B | A) \cdot P(A)}{P(B)} ] |

Here’s what each term represents:

( P(A B) ) is the probability of hypothesis A given that B has occurred. ( P(B A) ) is the probability of event B given hypothesis A is true. - ( P(A) ) is the prior probability of hypothesis A being true.

- ( P(B) ) is the marginal probability of event B.

Bayes’ Rule is particularly powerful in cases where we need to infer the likelihood of hypothesis A after observing some evidence B.

Bayesian methods have a wide array of applications:

- In medical diagnostics, they help in assessing the likelihood of a disease given specific symptoms.

- Machine learning leverages Bayesian classifiers, like the Naive Bayes classifier, for document and object categorization tasks.

- Spam filters use Bayes’ Theorem to determine the chances of an email being spam based on its content.

- Pattern recognition tasks, such as in computer vision, employ Bayesian methods to identify and classify patterns in images.

- In finance, the theorem aids in assessing the risk and potential return of investments based on past performance data.

The Naive Bayes model, a practical spin-off of Bayes’ Rule, simplifies assumptions by treating the features being observed as independent given the class label. Despite its “naive” approach, it remains effective and computationally efficient, making it a staple in classification tasks like document sorting, spam detection, sentiment analysis, and even medical diagnosis due to its computational simplicity and often surprisingly accurate performance.

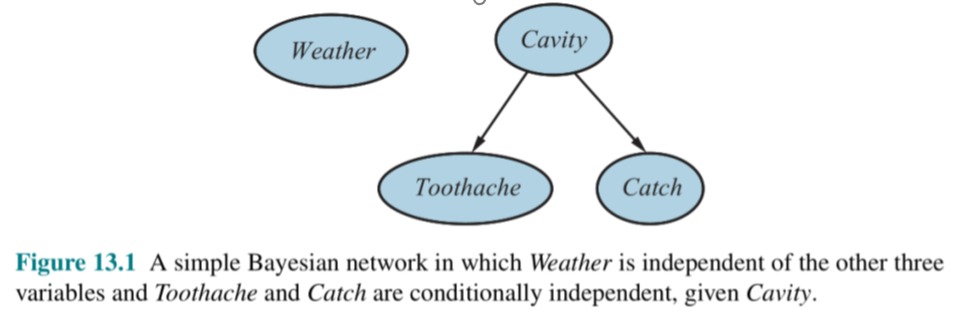

Bayesian Networks

Bayesian Networks, also referred to as Bayes Nets, are probabilistic graphical models that utilize a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) to depict dependencies among variables. These networks are invaluable across numerous fields including AI, statistics, and computer science for uncertainty modeling and probabilistic reasoning.

A Bayes Net is constructed using two key elements:

- Nodes: Each node symbolizes a random variable that can be either directly observed or latent (unobserved but influential). These nodes carry conditional probabilities detailing the likelihood of a node’s occurrence based on its parental nodes.

- Edges: Directed edges link nodes, illustrating dependency. An edge from node X to node Y implies that Y’s occurrence depends on X.

Bayesian Networks operate on three foundational principles:

- Markov Chain Principle: Variables are conditionally independent of non-descendants given their parents in the graph.

- Chain Rule Principle: The joint distribution across nodes is the product of conditional distributions, assuming each node is independent of non-descendants when conditioned on its parents.

- D-separation Principle: This outlines the conditions under which nodes are independent or dependent based on observations of other nodes.

Applications of Bayesian Networks are diverse, including:

- Medical Diagnostics: They map relationships between symptoms and diseases aiding in diagnoses.

- Recommendation Systems: They personalize user recommendations by analyzing user preferences and past behavior.

- Risk Analysis & Decision-Making: They assess risks in finance, insurance, and project management.

- Natural Language Processing: They model word dependencies to enhance understanding of natural language.

- Computational Biology: They study gene and protein interactions to unravel complex biological processes.

- Systems Engineering: They diagnose failures in complex systems with multiple interrelated components.

Advantages of Bayesian Networks include:

- Expressiveness: They effectively model complex variable relationships.

- Inference: They simplify conditional probability calculations and probabilistic inference.

- Uncertainty Management: They adeptly represent and manipulate data uncertainty and variability.

- Interpretability: Their graphical nature renders models intuitive and understandable.

- Easy Updating: They allow for straightforward model updates with new data inclusion.

For continuous variables, an important extension known as Continuous Bayesian Networks (CBNs) is employed. The primary distinction between traditional Bayes Nets and CBNs lies in how probability distributions are specified: CBNs use continuous functions for probability distributions, in contrast to the discrete tables used in traditional networks.

Inference

Inference is the intellectual process of drawing conclusions or making predictions about a phenomenon based on available evidence, data, or observations. It is a critical mechanism across various fields for hypothesis generation, decision-making, and knowledge construction. Here are the key facets of inference, succinctly summarized:

Statistical Inference: This involves making deductions about population parameters or testing hypotheses based on sample data. It is divided into two main types: descriptive inference, which summarizes data through metrics like means and standard deviations, and inductive inference, which generalizes findings from a sample to the broader population.

AI Inference: In artificial intelligence, inference is the process by which systems or models apply logical reasoning to arrive at conclusions or decisions, such as predicting outcomes or generating natural language responses based on input data.

Bayesian Inference: This approach treats probability as a degree of belief and involves updating beliefs in the light of new evidence using Bayes’ Theorem.

Deductive and Inductive Reasoning: Deductive reasoning draws specific conclusions from general premises, whereas inductive reasoning generalizes from specific observations to broader conclusions.

Philosophical Inference: In philosophy, inference is concerned with the construction of well-reasoned and justified arguments.

Scientific Inference: It is integral to formulating hypotheses, testing theories, and generalizing findings based on experimental or observational evidence in scientific practice.

Logical Inference: In logic, it refers to deriving new information from already established propositions, crucial in mathematics and computer science.

Inference is the practice of deriving new knowledge from existing information across disciplines, utilizing a mix of descriptive and inductive methods, deductive and inductive reasoning, and updating beliefs according to new evidence, particularly within frameworks like Bayesian inference.

Time and Uncertainty

Time and uncertainty in modeling refer to the incorporation of the temporal dimension when accounting for uncertain scenarios. Stochastic models like Markov chains and Markov decision processes exemplify this approach by considering how probabilities evolve over time.

For instance, in weather forecasting systems, time is a critical factor. Predictions for tomorrow hinge on today’s weather conditions, carrying inherent uncertainty. In essence, time adds a dynamic component to uncertainty, influencing how predictions and decisions are made in the face of changing conditions and information.

States and Observations

In practical applications, we often differentiate between ‘states’ and ‘observations.’ States represent the intrinsic conditions or characteristics of the system under study, while observations are the data collected about these states.

Take a navigation robot as an example: its ‘states’ include its current location, and its ‘observations’ are the data gathered from its sensors. These concepts are fundamental in fields such as robotics, where understanding and differentiating between the actual condition of the system and the data we obtain about it is crucial for tasks like navigation and decision-making.

Transition Model and Sensor Models

In stochastic systems, the transition model and sensor models are pivotal components.

The transition model details the likelihood of moving from one state to another, essentially defining the system’s dynamics, as seen in Markov chains.

Sensor models, on the other hand, describe the likelihood of making a particular observation from a specific state. These models are crucial in particle filtering and robotic localization.

For a navigation robot, the transition model would outline the chances of it moving from one spot to another, while the sensor model would indicate the probability of the robot’s sensors giving certain readings at its current location.

In summary, transition models help predict state changes over time, and sensor models relate these states to the data we observe. Both are integral to understanding and navigating complex, dynamic systems.

Inference in temporal models

Inference in temporal models is the process of deducing, forecasting, and comprehending the patterns of dynamic systems as they evolve. This method is crucial in domains such as time series analysis, dynamic systems, process control, and sequential event modeling. Here are the key concepts summarized:

Filtering: Estimating the current state of a system using present and past observations. It’s essential for real-time monitoring and state estimation updates.

Prediction: Calculating future states of a system based on current observations and states. This is vital for forward-looking decision-making and planning.

Smoothing: Revising past state estimates with all available observations. It’s used to refine past state estimations for improved accuracy.

Most Likely Explanation: Identifying the most probable sequence of states leading to observed data. This helps in understanding the underlying sequence of events in a system.

Learning in Temporal Models: Adjusting model parameters over time to reflect observed data. It’s key for adapting to changes in system dynamics and improving estimate precision.

- Inference Methods:

- Kalman Filters: Classic filtering for linear systems with Gaussian noise.

- Particle Filters: Used for non-linear and non-Gaussian systems.

- Rauch-Tung-Striebel Smoothing: A retrospective smoothing technique for linear Gaussian models.

- Viterbi Algorithm: Finds the most likely state sequence in Hidden Markov Models (HMMs).

- Challenges: Temporal inference can be computationally demanding, especially in complex systems or with substantial data. Inferring in non-linear and non-Gaussian systems often requires advanced methods like particle filters.

Temporal inference is pivotal in various applications, from weather forecasting to industrial process control and financial time series analysis. The choice of inference method depends on the system’s specific characteristics and the nature of the temporal data available.

The Hidden Markov Model (HMM)

The Hidden Markov Model (HMM) is a statistical model designed to analyze systems that are Markov processes with unknown parameters. The main challenge with HMMs is to infer these hidden parameters based on observable data.

While implementing an HMM from scratch in Python is complex, there are ready-to-use libraries like hmmlearn that simplify this task. HMMs are pivotal in various fields for analyzing sequences where the underlying processes are not directly observable but can be inferred from observable data.

Kalman Filters

Kalman Filters are a crucial tool in control theory and signal processing, employed for estimating the internal state of a linear dynamic system using a sequence of observable measurements over time.

Though implementing a Kalman Filter in Python from the ground up can be quite involved, there are several libraries, such as pykalman, which offer ready-to-use implementations. Kalman Filters are widely used for their efficiency in tracking and predicting the state of a system in real-time, especially in contexts with noisy measurement data.

Quantifying Uncertainties and Bayesian Networks

When tackling new problems involving uncertainties, it’s crucial to consider how these uncertainties can be represented and managed effectively. Bayesian Networks stand out as powerful tools for modeling problems with uncertainties and intricate relationships between various variables. These networks, also known as belief graphs or decision graphs, are directed acyclic graphs that encapsulate a set of variables and their conditional dependencies.

For instance, in medical diagnostics, a Bayesian Network can map the connections between various symptoms and diseases. The disease node in the network would be influenced by nodes representing different symptoms, allowing for a probabilistic assessment of the disease based on the presence of these symptoms.

To infer in Bayesian Networks, Monte Carlo sampling techniques like Gibbs Sampling and Metropolis-Hastings are often employed. Gibbs Sampling iteratively updates subsets of variables conditional on the others, whereas Metropolis-Hastings involves proposing transitions to new states which are accepted or rejected based on a defined probability. These methods enable effective inference in networks with complex relationships and uncertainties.

Probabilistic Reasoning Over Time and Kalman Filters

Probabilistic reasoning extends beyond static networks to address temporal changes and uncertainties. In such scenarios, models like Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Kalman Filters are instrumental.

The Kalman Filter, in particular, excels in integrating predictions from a physical model with noisy observational data to accurately estimate the real state of a system. This method has broad applications ranging from GPS location tracking and financial time series analysis to robotic system control.

In these models, Transition and Sensor Models are key components. The Transition Model details how the system’s state evolves over time, while the Sensor Model indicates the likelihood of various observations for different states.

For example, consider a robot navigating a 2D space. Its Transition Model might describe how its position changes based on actions like moving forward or turning. The Sensor Model might then predict the probability of the robot encountering obstacles at different locations. These models together enable the robot to navigate efficiently while accounting for uncertainties and dynamics of its environment.

Discussion

A practical and impactful contribution in the field of Quantifying Uncertainties and Bayesian Networks, Probabilistic Reasoning Over Time, and Kalman Filters could be the development of an advanced predictive maintenance system for industrial machinery. Here’s an outline of how this could be approached:

Project: Predictive Maintenance System Using Bayesian Networks, Probabilistic Reasoning, and Kalman Filters

Objective:

Develop an intelligent system that predicts equipment failure in industrial settings, thereby minimizing downtime and maintenance costs.

Components:

- Data Collection:

- Collect real-time data from machinery sensors (temperature, vibration, sound, pressure, etc.).

- Gather historical maintenance records and failure instances.

- Bayesian Networks:

- Use Bayesian Networks to model the probabilistic relationships between different sensor readings and machine states.

- Incorporate expert knowledge about machinery to structure the Bayesian Network, defining how different sensor readings influence the likelihood of potential failures.

- Probabilistic Reasoning Over Time:

- Implement algorithms that use historical data to understand how machine behavior evolves over time.

- Apply Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) to predict future states of the machinery based on observed data trends.

- Kalman Filters for Real-Time Analysis:

- Use Kalman Filters to process real-time sensor data for continuous estimation of the machine’s state.

- Continuously update and refine the machine’s state prediction as new data is received, improving prediction accuracy.

- Predictive Maintenance Algorithm:

- Develop an algorithm that analyzes the output from Bayesian Networks and Kalman Filters to predict potential failures.

- Set thresholds for alert generation, ensuring timely maintenance actions before actual failures occur.

- User Interface and Alert System:

- Create a dashboard to display real-time machine health, predictive alerts, and maintenance suggestions.

- Integrate an alert system to notify maintenance teams of upcoming maintenance needs.

Benefits:

- Reduced Downtime: By predicting failures before they occur, the system can schedule maintenance activities proactively, reducing unexpected downtime.

- Cost Efficiency: Preventative maintenance is more cost-effective than emergency repairs post-failure.

- Longevity of Equipment: Regular and timely maintenance can extend the life of machinery.

Application Areas:

- Manufacturing plants

- Power generation facilities

- Automotive industry

- Aerospace for aircraft maintenance

This system combines Bayesian Networks’ powerful data modeling capabilities with the dynamic state estimation of Kalman Filters, offering a sophisticated solution to one of the industry’s most pressing problems – unexpected equipment failure. The project can be a significant contribution to the field of industrial IoT and smart manufacturing.

Conclusion

Throughout our discussion, we’ve explored a range of sophisticated statistical and computational techniques crucial for understanding and managing uncertainty in various contexts. The concepts and models we delved into form the backbone of modern data analysis, predictive modeling, and decision-making under uncertainty.

We began by discussing the importance of statistical inference, which allows for making informed conclusions and predictions from data, laying the groundwork for understanding the broader implications of sample data.

The exploration of temporal modeling, particularly through Markov Models and Kalman Filters, highlighted the importance of accounting for the dimension of time in prediction and analysis. These models are pivotal in dynamic systems where conditions change over time, offering precision and reliability in continuously evolving scenarios.

Bayesian Networks stood out as a versatile framework for modeling complex dependencies under uncertainty. Their ability to incorporate prior knowledge and update beliefs with new evidence makes them a powerful tool in fields like medicine, finance, and artificial intelligence.

We also touched upon practical applications, such as the development of a predictive maintenance system using these techniques. This application underscored the real-world impact and potential of combining Bayesian Networks, Kalman Filters, and probabilistic reasoning in an industrial context, showcasing how these theoretical concepts can be applied to solve practical, impactful problems.

In conclusion, the amalgamation of these advanced techniques provides a comprehensive toolkit for tackling the challenges presented by uncertainty in data. Whether it’s in making sense of complex data sets, predicting future events, or optimizing systems and processes, the methodologies we’ve discussed are at the forefront of technological and analytical advancements. Their applications span numerous domains, demonstrating their versatility and indispensability in our increasingly data-driven world.

References

- Bzarg. (n.d.). How a Kalman Filter Works, in Pictures. Bzarg. From https://www.bzarg.com/p/how-a-kalman-filter-works-in-pictures/

- FilterPy. (n.d.). FilterPy Documentation. FilterPy. From https://filterpy.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Kalman filter. Wikipedia. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kalman_filter

- Labbe, R. (n.d.). Kalman and Bayesian Filters in Python. GitHub. From https://github.com/rlabbe/Kalman-and-Bayesian-Filters-in-Python

- Wikipedia. (n.d.). Bayesian network. Wikipedia. From https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bayesian_network

- Pgmpy. (n.d.). Pgmpy Documentation. Pgmpy. From http://pgmpy.org/

- Koller, D., & Friedman, N. (2009). Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques. MIT Press. From https://mitpress.mit.edu/books/probabilistic-graphical-models

- Geman, S., & Geman, D. (1984). Stochastic Relaxation, Gibbs Distributions, and the Bayesian Restoration of Images. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, PAMI-6(6), 721–741. https://doi.org/10.1109/tpami.1984.4767596

- Metropolis, N., Rosenbluth, A. W., Rosenbluth, M. N., Teller, A. H., & Teller, E. (1953). Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 21(6), 1087–1092. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1699114

- Kalman, R. E. (1960). A New Approach to Linear Filtering and Prediction Problems. Journal of Basic Engineering, 82(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3662552

- Norvig, P., & Russell, S. (2014). Inteligência artificial: Tradução da 3a Edição. Elsevier Brasil.

- JavaTpoint. (n.d.). The Wumpus World in Artificial Intelligence. From https://www.javatpoint.com/the-wumpus-world-in-artificial-intelligence

- BELLHOUSE, D. R., The Reverend Thomas Bayes, FRS: A Biography to Celebrate the Tercentenary of His Birth, Statistical Science, v. 19, n. 1, 2004.

- Professor’s slides and class material

- GPT-4.0, Bing AI, Bard AI (Used to improve the structure of the text, correct grammar and syntax)