Portfolio 4 IA

Introduction

Logical agents are a fascinating aspect of artificial intelligence, where machines make decisions based on logic and known information. To understand how they work, we delve into the realms of syntax and semantics in propositional logic.

Syntax, in this context, is like the grammar of a language but for logical statements. It’s about how we structure our logical sentences to organize our thoughts logically.

On the other hand, semantics is about the meaning of these sentences. Like understanding what someone means when they speak.

Logical agents use syntax to form logical sentences following specific rules, much like how we use grammar in language. Semantics helps them to understand what these sentences mean, like understanding a spoken language. This combination of syntax and semantics in propositional logic is what enables these agents to make smart, logical decisions in games and other applications.

Logical Agents

Knowledge-based agents in artificial intelligence (AI) are a fascinating topic, as they represent a sophisticated approach to AI that involves reasoning and decision-making based on internal knowledge representation. Here’s an exploration and structuring of the key elements of this theme:

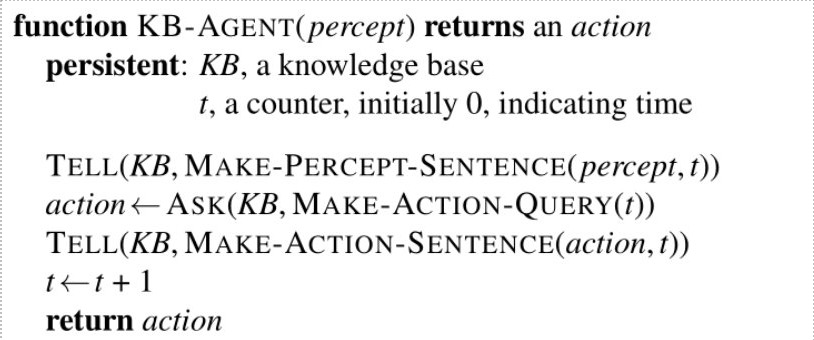

- Knowledge-Based Agents and Their Core Functionality:

- These agents use a reasoning process based on their internal knowledge representation to determine their actions.

- The essence of their functionality is to mimic human-like decision-making by using stored information.

- Knowledge Base (KB):

- The knowledge base is the central component of a knowledge-based agent.

- It consists of a set of sentences or statements about the world, representing the agent’s understanding and information.

- These sentences are structured in a specific knowledge representation language, making them interpretable by the agent.

- Nature of Sentences in KB:

- Sentences in the KB represent axioms or foundational truths when they are accepted without derivation from other sentences.

- Axioms form the basis from which other knowledge is inferred or derived.

- Key Operations: TELL and ASK:

- The KB must have mechanisms for adding new sentences (TELL) and querying existing knowledge (ASK).

- Both TELL and ASK operations may involve inference, which is the process of deriving new sentences based on existing ones.

- Inference and Consistency:

- Inference must adhere to the principle of consistency. This means that any new information or answer derived should be consistent with the previously accepted knowledge in the KB.

- Approaches to Building a KB:

- Declarative Approach: This involves starting with an empty KB and progressively adding sentences that the agent requires to function in a specific environment. It’s akin to teaching the agent facts one by one.

- Procedural Approach: This approach bypasses the traditional KB structure and encodes behaviors and knowledge directly as program code, integrating knowledge into the agent’s operational logic.

Knowledge-based agents in AI represent an advanced approach where agents are equipped with a knowledge base that acts like a repository of information and axioms.

These agents use logical reasoning to make decisions and answer queries, making them capable of handling complex tasks that require an understanding of the world they operate in. The development of these agents can follow either a declarative approach, where knowledge is explicitly stated, or a procedural approach, where knowledge is embedded in the code.

Syntax and Semantics

Exploring the intricate relationship between syntax and semantics in linguistics reveals how these components interact to shape our understanding of language and logic. Let’s delve into these concepts and structure our discussion:

- Syntax: Structuring Sentences

- Syntax is the linguistic component responsible for the arrangement and interconnection of sentence constituents, providing structure.

- A well-constructed sentence, such as (x + y = 4), follows the syntactic rules, ensuring clarity and comprehensibility.

- In contrast, a poorly structured sentence like (x4y+=) lacks syntactic coherence, leading to confusion.

- Model Theory in Syntax

- The concept of model theory extends into syntax. When we say (M(\alpha) \subseteq M(\beta)), it means the set of models (or interpretations) that make (\alpha) true is contained within those that make (\beta) true.

- In logical terms, (\alpha \models \beta) indicates that (\beta) is true whenever (\alpha) is true.

- Semantics: Meaning and Interpretation

- Semantics deals with the meanings of words and the interpretation of sentences.

- It defines the truth of sentences in various models or possible worlds. For instance, the arithmetic statement (x + y = 4) is true in a world where (x = 2) and (y = 2), but false where (x = 1) and (y = 1).

- Satisfaction and Models in Semantics

- If a sentence (\alpha) is true in a model (m), we say (m) satisfies (\alpha) or (m) is a model of (\alpha).

- The logical relationship between sentences is expressed as (\alpha \models \beta), meaning (\alpha) is a logical consequence of (\beta).

- Logical Implications and Inference

- An example can illustrate this: In every model where a knowledge base (KB) is true, a sentence (\alpha1) might also be true, leading to (KB \models \alpha1).

- Conversely, if in some models where KB is true, (\alpha2) is false, then KB does not imply (\alpha2).

- This demonstrates how logical implication aids in deriving conclusions or performing logical inference.

- Inference Algorithms

- If an inference algorithm (i) can derive (\alpha) from KB, we express this as (i) derives (\alpha) from KB.

- A complete inference algorithm can derive any sentence that is logically related to the KB.

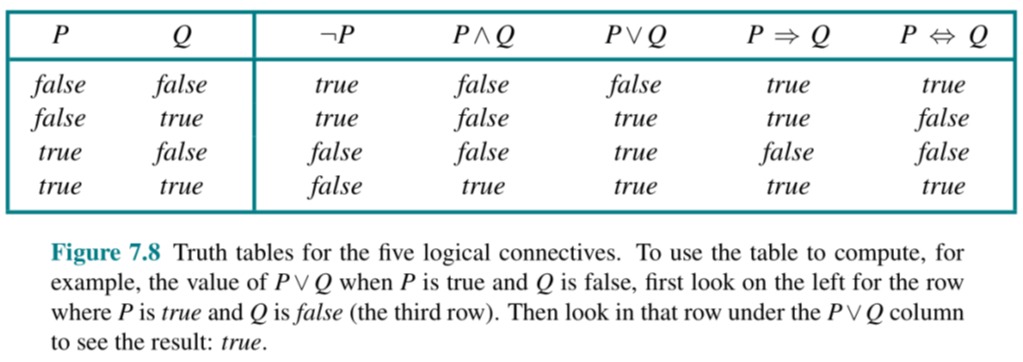

- Logical Connectives

- Negation ((\neg)): Denies the truth of a sentence, like (\neg W1,3).

- Conjunction ((\land)): Connects two statements in an ‘and’ relationship, such as (W1,3 \land P3,1).

- Disjunction ((\lor)): Connects statements in an ‘or’ relationship, like (W1,3 \lor P3,1).

- Implication ((\Rightarrow)): A conditional statement, where one statement implies another, e.g., ((W1,3 \land P3,1) \Rightarrow \neg W2,2).

- Biconditional ((\Leftrightarrow)): States that two sentences are equivalent, as in (W1,3 \Leftrightarrow \neg W2,2).

- Exclusive or ((\oplus)): Often symbolized as (\oplus), it denotes a relationship where either of the statements is true, but not both.

Sentence grammar in propositional logic, along with operator precedences, from highest to lowest.

For complex sentences, we have five rules, which are valid for any sub-sentences P and Q (atomic or complex) in any model m (“if and Only if - IFF” ):

¬P is true if P is false in m.

P∧Q is true iff P and Q are true in m.

P∨Q is true if P or Q is true in m.

P ⇒ Q is true unless P is true and Q is false in m.

P ⇔ Q is true iff P and Q are both true or both false at m.

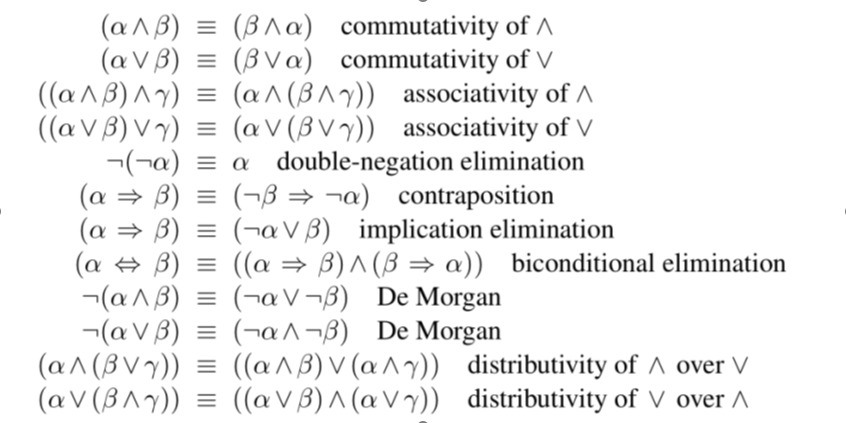

Logical equivalences:

The inferences discussed so far are solid;

We must also consider completeness for the inference algorithms that use them;

Search algorithms such as Iterative deepening search are complete in the sense that they will find any achievable objective;

If the available rules of inference are inadequate, then the goal is not achievable - no proof exists that uses only these rules of inference.

The resolution inference rule leads to a complete inference algorithm when paired with some search algorithm.

Minesweeper Solver

- Definition: Given a 2D array arr[][] of dimensions N*M, representing a minesweeper matrix, where each cell contains an integer from the range [0, 9], representing the number of mines in itself and all the eight cells adjacent to it, the task is to solve the minesweeper and uncover all the mines in the matrix. Print ‘X’ for the cell containing a mine and ‘_’ for all the other empty cells. If it is not possible to solve the minesweeper, then print “-1”.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Input:

arr[][] = {1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1},

{2, 3, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2},

{3, 5, 3, 2, 1, 2, 2},

{3, 6, 5, 3, 0, 2, 2},

{2, 4, 3, 2, 0, 1, 1},

{2, 3, 3, 2, 1, 2, 1},

{1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0}.

Output:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

x _ _ _ _ x _

_ x x _ _ _ x

x _ x _ _ _ _

_ x x _ _ _ x

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ x _ _ x _ _

Input:

arr[][] = {0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1},

{0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1},

{0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1},

{0, 0, 2, 2, 2, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 2, 2, 2, 0, 0},

{0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0}

Output:

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ x

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

_ _ _ x _ _ _

_ _ _ x _ _ _

_ _ _ _ _ _ _

Approach: The given problem can be solved using Backtracking. The idea is to iterate over each cell of a matrix, based on the information available from the neighboring cells, assign a mine to that cell or not.

Follow the below steps to solve the given problem:

Initialize a matrix, say grid[][], and visited[][] to store the resultant grid and keep the track of visited cells while traversing the grid. Initialize all grid values as false.

Declare a recursive function solveMineSweeper() to accept arrays arr[][], grid[][], and visited[][] as a parameter.

If all the cells are visited and a mine is assigned to the cells satisfying the given input grid[][], then return true for the current recursive call.

If all the cells are visited but the solution is not satisfying the input grid[], return false for the current recursive call.

If the above two conditions are found to be false, then find an unvisited cell (x, y) and mark (x, y) as visited.

If a mine can be assigned to the position (x, y), then perform the following steps:

Mark grid[x][y] as true.

Decrease the number of mine of the neighboring cells of (x, y) in the matrix arr[][] by 1.

Recursively call for solveMineSweeper() with (x, y) having a mine and if it returns true, then a solution exists. Return true for the current recursive call.

Otherwise, reset the position (x, y) i.e., mark grid[x][y] as false and increase the number of mines of the neighboring cells of (x, y) in the matrix arr[][] by 1.

If the function solveMineSweeper() with (x, y) having no mine, returns true, then it means a solution exists. Return true from the current recursive call.

If the recursive call in the above step returns false, that means the solution doesn’t exist. Therefore, return false from the current recursive calls.

If the value returned by the function solveMineSweeper(grid, arr, visited) is true, then a solution exists. Print the matrix grid[][] as the required solution. Otherwise, print “-1”.

Below is the implementation of the above approach

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

// C++ program for the above approach

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

// Stores the number of rows

// and columns in given matrix

int N, M;

// Maximum number of rows

// and columns possible

#define MAXM 100

#define MAXN 100

// Directional Arrays

int dx[9] = { -1, 0, 1, -1, 0, 1, -1, 0, 1 };

int dy[9] = { 0, 0, 0, -1, -1, -1, 1, 1, 1 };

// Function to check if the

// cell (x, y) is valid or not

bool isValid(int x, int y)

{

return (x >= 0 && y >= 0 && x < N && y < M);

}

// Function to print the matrix grid[][]

void printGrid(bool grid[MAXN][MAXM])

{

for (int row = 0; row < N; row++) {

for (int col = 0; col < M; col++) {

if (grid[row][col])

cout << "x ";

else

cout << "_ ";

}

cout << endl;

}

}

// Function to check if the cell (x, y)

// is valid to have a mine or not

bool isSafe(int arr[MAXN][MAXM], int x, int y)

{

// Check if the cell (x, y) is a

// valid cell or not

if (!isValid(x, y))

return false;

// Check if any of the neighbouring cell

// of (x, y) supports (x, y) to have a mine

for (int i = 0; i < 9; i++) {

if (isValid(x + dx[i], y + dy[i])

&& (arr[x + dx[i]][y + dy[i]] - 1 < 0))

return (false);

}

// If (x, y) is valid to have a mine

for (int i = 0; i < 9; i++) {

if (isValid(x + dx[i], y + dy[i]))

// Reduce count of mines in

// the neighboring cells

arr[x + dx[i]][y + dy[i]]--;

}

return true;

}

// Function to check if there

// exists any unvisited cell or not

bool findUnvisited(bool visited[MAXN][MAXM], int& x, int& y)

{

for (x = 0; x < N; x++)

for (y = 0; y < M; y++)

if (!visited[x][y])

return (true);

return (false);

}

// Function to check if all the cells

// are visited or not and the input array

// is satisfied with the mine assignments

bool isDone(int arr[MAXN][MAXM], bool visited[MAXN][MAXM])

{

bool done = true;

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < M; j++) {

done

= done && (arr[i][j] == 0) && visited[i][j];

}

}

return (done);

}

// Function to solve the minesweeper matrix

bool SolveMinesweeper(bool grid[MAXN][MAXM],

int arr[MAXN][MAXM],

bool visited[MAXN][MAXM])

{

// Function call to check if each cell

// is visited and the solved grid is

// satisfying the given input matrix

bool done = isDone(arr, visited);

// If the solution exists and

// and all cells are visited

if (done)

return true;

int x, y;

// Function call to check if all

// the cells are visited or not

if (!findUnvisited(visited, x, y))

return false;

// Mark cell (x, y) as visited

visited[x][y] = true;

// Function call to check if it is

// safe to assign a mine at (x, y)

if (isSafe(arr, x, y)) {

// Mark the position with a mine

grid[x][y] = true;

// Recursive call with (x, y) having a mine

if (SolveMinesweeper(grid, arr, visited))

// If solution exists, then return true

return true;

// Reset the position x, y

grid[x][y] = false;

for (int i = 0; i < 9; i++) {

if (isValid(x + dx[i], y + dy[i]))

arr[x + dx[i]][y + dy[i]]++;

}

}

// Recursive call without (x, y) having a mine

if (SolveMinesweeper(grid, arr, visited))

// If solution exists then return true

return true;

// Mark the position as unvisited again

visited[x][y] = false;

// If no solution exists

return false;

}

void minesweeperOperations(int arr[MAXN][MAXN], int N,

int M)

{

// Stores the final result

bool grid[MAXN][MAXM];

// Stores whether the position

// (x, y) is visited or not

bool visited[MAXN][MAXM];

// Initialize grid[][] and

// visited[][] to false

memset(grid, false, sizeof(grid));

memset(visited, false, sizeof(visited));

// If the solution to the input

// minesweeper matrix exists

if (SolveMinesweeper(grid, arr, visited)) {

// Function call to print the grid[][]

printGrid(grid);

}

// No solution exists

else

printf("No solution exists\n");

}

// Driver Code

int main()

{

// Given input

N = 7;

M = 7;

int arr[MAXN][MAXN] = {

{ 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1 }, { 2, 3, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2 },

{ 3, 5, 3, 2, 1, 2, 2 }, { 3, 6, 5, 3, 0, 2, 2 },

{ 2, 4, 3, 2, 0, 1, 1 }, { 2, 3, 3, 2, 1, 2, 1 },

{ 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0 }

};

// Function call to perform

// generate and solve a minesweeper

minesweeperOperations(arr, N, M);

return 0;

}

To know more about the problem and see other imnplemantations of it go to https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/minesweeper-solver/

A Minesweeper Solver is an excellent example of how logical agents operate, particularly in terms of knowledge acquisition, storage, and decision-making based on that knowledge. In Minesweeper, the agent (the solver program) must uncover all non-mined squares without detonating a mine, using logical reasoning to deduce where mines are located. Let’s delve deeper into how logical agents apply in the context of Minesweeper, focusing on syntax and semantics in propositional logic:

Logical Agents in Minesweeper:

- Knowledge Acquisition:

- Initially, the agent has limited knowledge: the size of the grid and the rule that numbers on revealed squares indicate the count of adjacent mines.

- As the game progresses, the agent uncovers squares and gains more information.

- Knowledge Storage:

- The agent stores the information from each action, like the number of adjacent mines for each revealed square.

- Decision-Making:

- Based on stored knowledge, the agent makes logical deductions to decide which squares are safe to reveal next.

- The agent must also sometimes take calculated risks when the information is insufficient for a certain deduction.

Syntax and Semantics in Minesweeper’s Propositional Logic:

In Minesweeper, propositional logic is used to formalize the knowledge and reasoning process. Here’s how syntax and semantics come into play:

- Syntax - Propositional Variables:

- Each square on the grid can be represented by a propositional variable, e.g., ( P_{i,j} ) could represent the proposition “There is a mine at square (i, j)”.

- Numbers on squares translate into specific syntactical structures. For instance, a “2” on a square might translate to two mines in its adjacent squares.

- Syntax - Logical Connectives:

- Logical connectives like AND ((\land)), OR ((\lor)), and NOT ((\neg)) are used.

- For instance, if a square has a “1”, and there’s only one adjacent unrevealed square, the agent deduces that this square must contain a mine (( P )).

- Semantics - Interpreting Propositions:

- The semantics involves interpreting these propositions. For example, if ( P_{i,j} ) is true, it means there is indeed a mine at (i, j).

- The agent uses semantics to understand the implications of the syntactic structures it forms.

- Semantics - Rules of Inference:

- Rules like modus ponens (if ( P ) implies ( Q ), and ( P ) is true, then ( Q ) is also true) are used for making deductions.

- For example, if the agent knows ( P_{i,j} ) (there’s a mine at (i, j)), and ( P_{i,j} ) implies ( Q_{k,l} ) (another square (k, l) is dangerous), then the agent deduces ( Q_{k,l} ).

Example Scenarios in Minesweeper:

Scenario 1: A square reveals the number 1, and it has only one adjacent unrevealed square. The agent deduces that this unrevealed square must contain a mine.

Scenario 2: A square shows the number 2, and the agent has already identified one mine in its vicinity. If there’s only one other unrevealed square adjacent to it, the agent deduces that this square also contains a mine.

Conclusion

In conclusion, logical agents, with their use of syntax and semantics in propositional logic, play a crucial role in the world of artificial intelligence.

Minesweeper serves as a practical and engaging example of a logical agent in action. The solver uses syntax to structure its knowledge about the game board and semantics to interpret and reason about this information, making decisions based on the logical inferences drawn from its accumulated knowledge. This process exemplifies the core functionalities of logical agents: acquiring knowledge from the environment, storing this knowledge, and using it to make informed decisions.

The real-world applications of these agents are vast and impactful. From playing games like Tic-Tac-Toe or chess, where they decide the next best move, to more complex tasks like helping doctors diagnose diseases or aiding in environmental monitoring, their utility is widespread. In all these applications, the agents use the rules of logic (syntax) to process information and then interpret this information (semantics) to make decisions or predictions.

The importance of logical agents lies in their ability to automate and enhance decision-making processes in various fields. They bring precision, efficiency, and often, a level of insight that might be challenging for humans due to the complexity or volume of data. As technology continues to advance, the role of these logical agents, with their foundation in syntax and semantics, is set to become even more integral in solving complex problems and aiding in technological progress.

References

- https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/minesweeper-solver/