Portfolio 1 IA

Introduction

What is intelligence, and what is artificial intelligence? These are profound questions that we will explore from a particular perspective.

To embark on this journey, it’s crucial to first establish a foundation by delving into the historical context of intelligence, understanding its implications in various fields, including art, and dissecting both the advantages and potential risks associated with artificial intelligence. However, before we dive into these complex realms, we must grasp the fundamental definitions.

According to the dictionary, intelligence is the capacity for learning, comprehending, and effectively dealing with new and challenging situations. It encompasses the use of reason, application of knowledge, and the ability to comprehend the world around us.

On the other hand, the term ‘artificial’ is simpler to define—it refers to something created by humans. However, the dictionary does not provide an explicit definition of ‘Artificial Intelligence,’ which leads us to contemplate its essence.

Building upon the interpretations of prominent figures like IBM and pioneers in the field such as Russell and Norvig, Artificial Intelligence can be summarized as a machine capable of mimicking human behaviors and cognitive processes. It is this definition that forms the basis of our exploration into the intriguing world of intelligence and artificial intelligence.

Content

In this section, we delve deeper into the world of Artificial Intelligence, exploring key concepts, the Turing Test, contemporary AI models, and the prevailing standard model.

The Turing Test

The Turing Test, a pivotal concept in AI, can be divided into several components:

- Processing Natural Language: The ability to communicate with humans effectively.

- Representation of Knowledge: Storing and managing acquired knowledge.

- Automated Reasoning: Capable of answering questions and drawing new conclusions.

- Machine Learning: Adapting to new situations and identifying patterns.

- Computer Vision and Speech Recognition: Understanding the world.

- Robotics: Manipulating objects and mobility.

This test goes beyond solving problems correctly; it assesses the sequence and timing of reasoning steps in comparison to human problem-solving.

Modern Applications of AI

Beyond definitions and testing, let’s explore how AI is utilized in contemporary scenarios.

Acting Rationally

The rational agent concept is fundamental. An AI system should:

- Operate autonomously.

- Perceive its environment.

- Persist over an extended duration.

- Adapt to changes.

- Establish and pursue goals.

Rationality standards are mathematically well-defined and universal, serving as a foundation for agent designs proven to achieve their objectives.

The Standard Model

- Historically, the rational agent approach has been the cornerstone of AI.

- AI emphasizes creating agents that make the “right” decisions based on provided objectives.

- The definition of the “right thing” depends on the objective set for the agent.

- This approach is so prevalent that it’s often termed the standard model.

Challenges with the Standard Model

While the standard model has guided AI research effectively, it may not be suitable in the long run. It assumes we can fully and accurately specify the machine’s objective.

In practical, real-world scenarios, defining objectives becomes increasingly challenging, as seen in autonomous cars.

The misalignment between our true preferences and machine-programmed goals is known as the value alignment problem, leading to adverse consequences when objectives are wrongly specified.

Observations on this Introduction

Adaptations to the standard model are essential, considering the computational tractability of the problem and the necessity for machines to pursue objectives beneficial to humanity, even when objectives are uncertain.

Artificial Intelligence draws from various fields, including philosophy, mathematics, economics, neuroscience, psychology, computer engineering, control, cybernetics, and linguistics, among others, making it a multidisciplinary endeavor.

History

In this section, we’ll explore the historical development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) from its early conceptualizations to its resurgence in modern times.

Early Notions of AI

In the year 1863, English author Samuel Butler, also known as Cellarius, authored “Darwin among the Machines,” which was published in the newspaper The Press. This article, one of the earliest discussions of AI, predated the formal definition of AI. It posited the idea that machines could exhibit a form of mechanistic life, akin to Darwinian natural selection, suggesting an evolutionary path where machines could eventually surpass humans in dominance.

The First AI Encounters

Defining the first AI is a challenge, but early examples include the mythological creature Talos from Mitology and Ficcion, dating back to 400 A.C. Talos was a giant copper-made robot designed to act as a guardian of Crete.

The Emergence of AI (1943 - 1956)

The foundations of AI were laid by Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts through a neuron model, where neurons could be in an “on” or “off” state based on stimulation from neighboring neurons. This marked a significant precursor in the AI field.

Alan Turing made influential contributions in this period, introducing concepts like the Turing test, machine learning, genetic algorithms, and reinforcement learning. Turing’s insight suggested that developing learning algorithms and teaching machines would be more efficient than manually programming their intelligence.

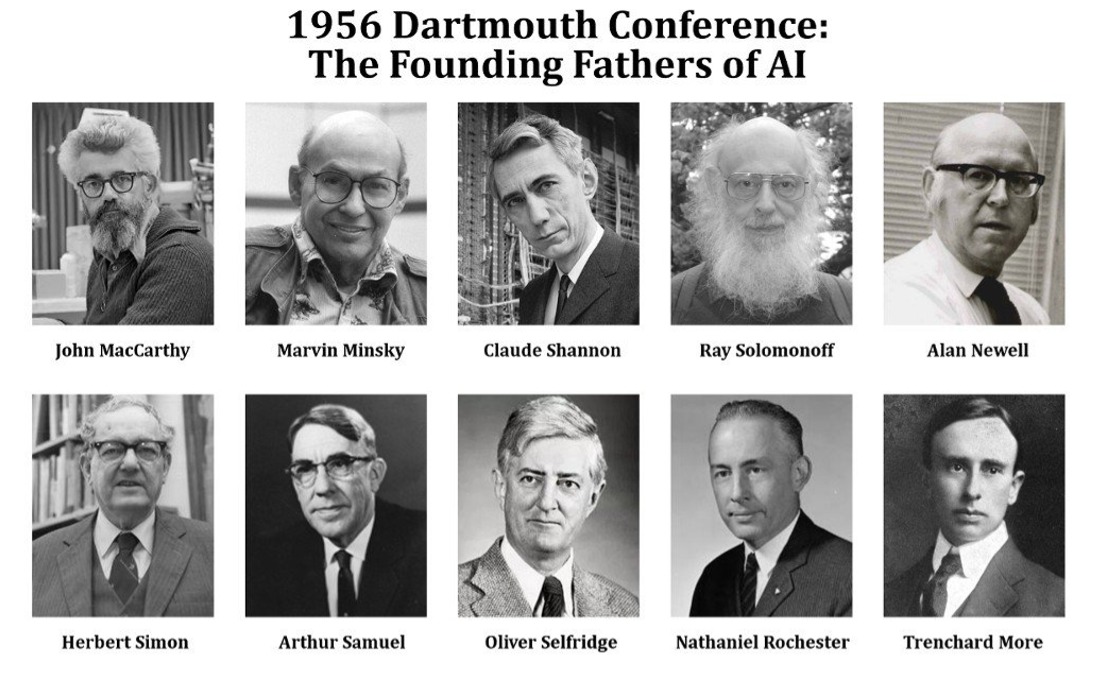

In 1956, AI gained further recognition with significant events.

Great Expectations for AI

The era of AI development saw notable experiments, such as Herbert Gelernter’s Geometry Theorem Prover, which could prove complex theorems, and Arthur Samuel’s work in reinforcement learning for playing checkers.

However, a realization emerged: machines could only learn what they could represent, and their representational capabilities were limited. As a response, specialized systems emerged, preparing the AI’s domain knowledge, enabling them to tackle problems more effectively. This gave rise to high expectations for AI, leading to significant investments and technological advancements.

The Winter

Despite these great expectations, the AI industry faced a downturn in 1986. Projects and companies struggled to deliver on their promises within short timelines, casting doubt on the feasibility of AI. Challenges included building and maintaining expert systems for complex domains, especially when faced with uncertainty and the inability to learn from experience.

The Return of AI (1987)

In the late 1980s, the AI field experienced a resurgence. Multiple groups rediscovered the backpropagation learning algorithm initially developed in the 1960s. Connectionist models that formed internal concepts more aligned with the real world began to emerge. These models were adaptable and could learn from examples, showing promise for future applications.

Rich Sutton introduced reinforcement learning concepts in 1988, used in areas like Markov decision processes. This period marked the gradual convergence of AI subfields, including computer vision, robotics, speech recognition, multi-agent systems, and natural language processing.

The Era of Big Data

Advancements in computing power and the birth of the World Wide Web enabled the creation of massive datasets, often referred to as “big data.” These datasets encompass vast amounts of text, images, speech, video, genomic data, and more. Learning algorithms specifically designed for big data emerged during this period.

The Rise of Deep Learning

Deep learning, a machine learning approach involving multiple layers of simple, tunable computing elements, had been used since the 1970s but gained prominence in 2011. It revolutionized speech recognition and object recognition. The 2012 ImageNet competition, where a deep learning system excelled, marked a significant milestone. Deep learning achieved breakthroughs in speech recognition, machine translation, medical diagnostics, and game-playing, such as AlphaGo’s victory over a human world champion in 2016.

These achievements rekindled interest in AI across various sectors, including education, business, investment, government, media, and the public.

Summing It Up

- In the 1960s, AI focused on inference by search, but the lack of sufficient material for AI led to a “winter.”

- In 1987, AI shifted toward inference by knowledge, expanding the scope but also increasing complexity, resulting in the second “winter.”

- Between 1998 and 2012, AI made significant progress in reasoning by learning, particularly in deep learning, which remains a foundational aspect of AI today.

Neats vs. Scruffies

A distinction emerged between “Neats” and “Scruffies.” Neats advocated grounding AI theories in mathematical rigor, while Scruffies preferred experimenting with various ideas and evaluating their practicality. In the 1990s and 21st century, AI research predominantly adopted Neat approaches, but the recent emphasis on deep learning signifies a resurgence of Scruffies’ influence.

AI Nowadays

In the contemporary landscape, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is advancing rapidly, and its influence is felt across various domains. This section provides an overview of the current state of AI, highlighting key statistics and achievements.

AI Index 2018-2019

Enrollment in AI disciplines has surged, increasing by 5 times in the US and 16 times internationally.

AI has become the most popular specialization within computer science.

The AI workforce is predominantly male, comprising 80%, while 20% are female.

Attendance at the NeurIPS conference has surged by 800% since 2012, with other conferences experiencing a 30% increase.

China, Europe, and the USA lead in the number of AI publications.

The field has witnessed a 20-fold growth in AI publications from 2010 to 2019.

The main topics of focus include machine learning, computer vision, and natural language.

Countries such as Singapore, Brazil, Australia, Canada, and India have seen the highest growth in AI-related hires.

AI startups in the US have increased twentyfold.

The speed of training for image recognition tasks has seen a remarkable drop of x100 in two years.

The computing power used in leading AI applications is doubling every 3.4 months.

AI systems have surpassed or equaled human performance in various domains, including games like chess, Go, poker, Pac-Man, Jeopardy!, image recognition, speech recognition, and more.

Current Capabilities of AI

AI’s capabilities have expanded significantly. Here are some examples:

AI-powered robots like BigDog and Atlas can navigate through various terrains with legged locomotion.

Programs such as NASA’s Remote Agent enable autonomous navigation and control of aircraft.

DART (Dynamic Analysis and Replanning Tool) manages logistics for 50,000 vehicles with different loads and destinations.

Services like Uber and Google Maps use AI for navigation.

AI-driven automatic translation covers 99% of human languages, and it approaches human-level performance for languages like English and French.

Speech recognition has improved to a 5.1% error rate, closing in on human performance.

Voice-based interactions now account for 33% of human-machine interactions globally, with platforms like Alexa, Siri, Cortana, and Google Assistant leading the way.

Recommendations from companies like Amazon, Facebook, Netflix, Spotify, YouTube, and Walmart are driven by machine learning algorithms that analyze user history and preferences.

Advanced spam filters employ deep learning to analyze content, including text, music, and video, in addition to history and metadata.

Medicine

AI algorithms now match or surpass medical experts in diagnosing many conditions, particularly in image-based diagnostics. Examples include Alzheimer’s, metastatic breast cancer, ophthalmological diseases, and skin diseases.

The FDA approved 12 medical applications of AI in 2018, indicating growing trust in AI’s diagnostic capabilities.

Art

In 2022, a piece of art generated by AI won first place in the Colorado State Fair fine arts competition, underscoring AI’s creative potential.

Coding:

There is too many examples to show just here but Open AI, GPT-4, Bing AI, etc. Is able to code even complex codes and help to find erros in codes that already exist

Here is a exemple :

My text: Good morning, could you show me a Python code that plots a 1 Hz sinusoid with phase 0 in black, a 1 Hz sinusoid with phase -pi/2 in red and a 1 Hz sinusoid with phase pi/2 in blue . The sampling frequency is 40 Hz, the Y axis should be magnitude and the X axis should be time in seconds. Show approximately 4 seconds on the graph. In a second plot I want to see the Fourier spectrum of the 60 Hz sinusoid with zero phase.

AI: Certainly! Here is a Python code that plots the 1 Hz sinusoids with the specified phases in black, red, and blue, respectively. The Y-axis represents magnitude, and the X-axis represents time in seconds. The graph shows approximately 4 seconds of data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Sampling frequency

fs = 40

# Time vector

t = np.arange(0, 4, 1/fs)

# 1 Hz sinusoid with phase 0 in black

y1 = np.sin(2*np.pi*t)

# 1 Hz sinusoid with phase -pi/2 in red

y2 = np.sin(2*np.pi*t - np.pi/2)

# 1 Hz sinusoid with phase pi/2 in blue

y3 = np.sin(2*np.pi*t + np.pi/2)

# Plotting the three sinusoids

plt.plot(t, y1, 'k', label='Phase 0')

plt.plot(t, y2, 'r', label='Phase -π/2')

plt.plot(t, y3, 'b', label='Phase π/2')

# Setting plot parameters

plt.xlabel('Time (s)')

plt.ylabel('Magnitude')

plt.title('Three 1 Hz Sinusoids with Different Phases')

plt.legend()

# Displaying the plot

plt.show()

AI: Here is a Python code that plots the Fourier spectrum of a 60 Hz sinusoid with zero phase:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Sampling frequency

fs = 1000

# Time vector

t = np.arange(0, 1, 1/fs)

# 60 Hz sinusoid with zero phase

y = np.sin(2*np.pi*60*t)

# Computing the Fourier transform of the signal

Y = np.fft.fft(y)

# Computing the frequency vector for plotting the spectrum

f = np.linspace(0, fs/2, len(Y)//2)

# Plotting the spectrum

plt.plot(f, abs(Y[:len(Y)//2]))

# Setting plot parameters

plt.xlabel('Frequency (Hz)')

plt.ylabel('Magnitude')

plt.title('Fourier Spectrum of a 60 Hz Sinusoid with Zero Phase')

# Displaying the plot

plt.show()

Benefits of AI

AI offers numerous advantages in various domains:

Robotics: AI can automate repetitive and hazardous tasks, enhance productivity, and reduce labor costs.

Autonomous Weapons: Scalable technologies similar to autonomous vehicles can improve military capabilities.

Surveillance: AI enables monitoring of vast amounts of data, such as phone conversations, videos, emails, and social media, to identify suspicious activities.

Decision Making: AI accelerates decision-making processes, optimizing services, increasing company profits, and minimizing risks.

Critical Security Applications: AI can enhance the safety and efficiency of cargo transportation, energy distribution, and more.

Cybersecurity: AI can detect and prevent cyberattacks, from viruses and malware to phishing and fake news.

Human-Level AI: AI accelerates scientific discoveries and can tackle complex problems.

Risks of AI

Despite its potential, AI presents several challenges:

Robotics: Automation can lead to significant job displacement and increased poverty.

Autonomous Weapons: The scalability of autonomous weapon technologies raises ethical concerns.

Surveillance: Increased surveillance raises privacy and political usage concerns.

Decision Making: Unintended biases may emerge if decision-making rules are not carefully designed.

Critical Security Applications: Ethical considerations must be taken into account.

Cybersecurity: Misused AI can stifle free expression and privacy.

Human-Level AI: Renowned AI scientists and figures like Stephen Hawking, Bill Gates, and Elon Musk have expressed concerns about the potential risks of advanced AI.

Past Incidents

Notable AI-related incidents, such as the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica scandal, highlight the importance of ethical and responsible AI practices in the age of big data and privacy concerns.

Agents and Environments

Understanding the interplay between AI agents and their environments is essential. Key concepts include:

Agent’s Action: Depends on the agent’s internal programming and all previously observed perceptions.

Agent Function: Maps percept sequences to actions.

Agent Program: Implements the agent function in an artificial system.

Rationality

Consequentialism emphasizes actions that maximize positive consequences and minimize negative ones.

The performance measure defines success criteria, and it may be explicit or implicit.

Rationality is not synonymous with perfection; it maximizes expected performance, while perfection maximizes performance.

Intelligent agents engage in information acquisition, decision-making, and learning.

Environments

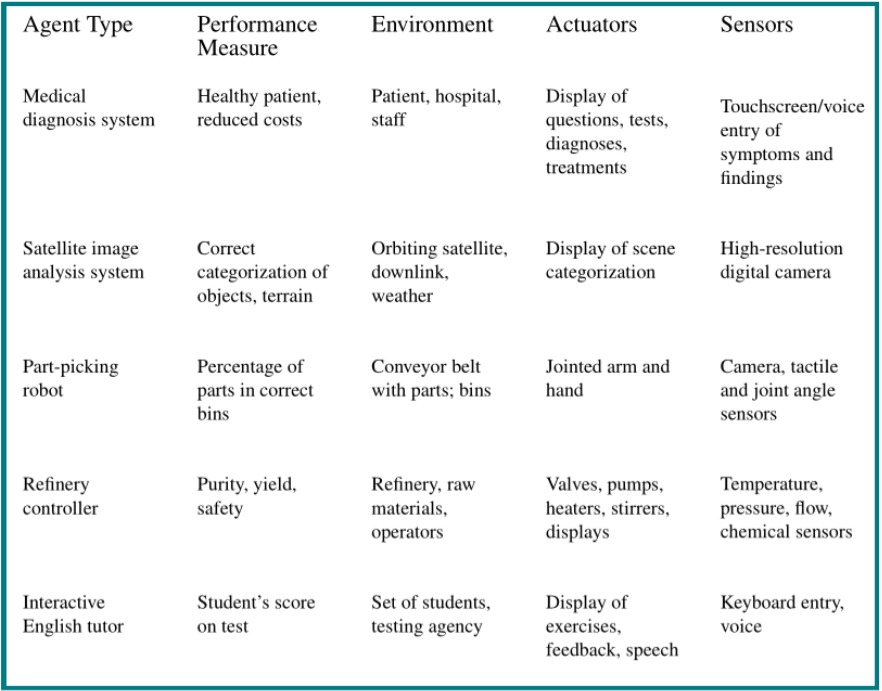

When designing an agent, the first step should always be to specify the task environment as completely as possible;

Description PEAS (Performance, Environment, Actuators, Sensors):

What is the desired performance measure?

What is the task environment like?

What actuators are available to perform actions?

What sensors are available to explore the environment?

Specifying the task environment

Specifying the task environment

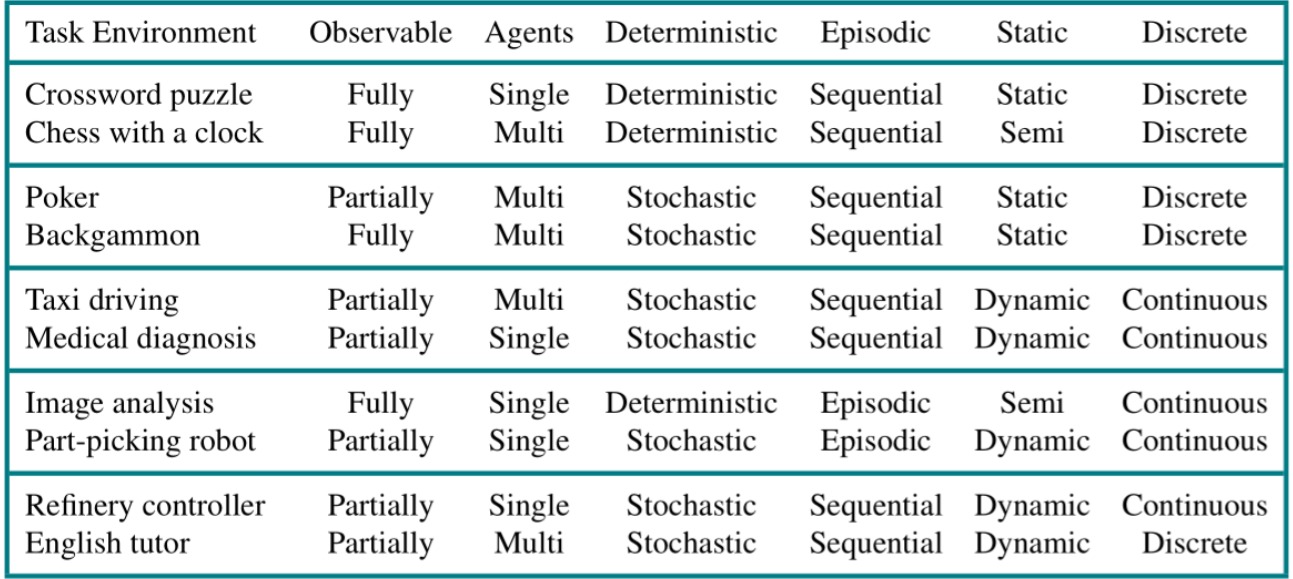

Task environment properties

Fully observable vs. Partially observable vs. partially observable Not observable;

Single agent vs. single agent Multiagent;

Deterministic vs. Non-deterministic;

Episodic vs. Sequential;

Static vs. Dynamic;

Discreet vs. Continuous;

Known vs. Unknown;

Agent Architecture

Agent architecture: Computational device with physical sensors and actuators.

AGENT = PROGRAM + ARCHITECTURE

Agent Program

Agents built using a table-oriented approach PROBLEM!

Example: A lookup table for a chess game would have entries!

Solution: Strategies that guarantee a smaller program (e.g. Newton’s method for calculating square roots);

Principles

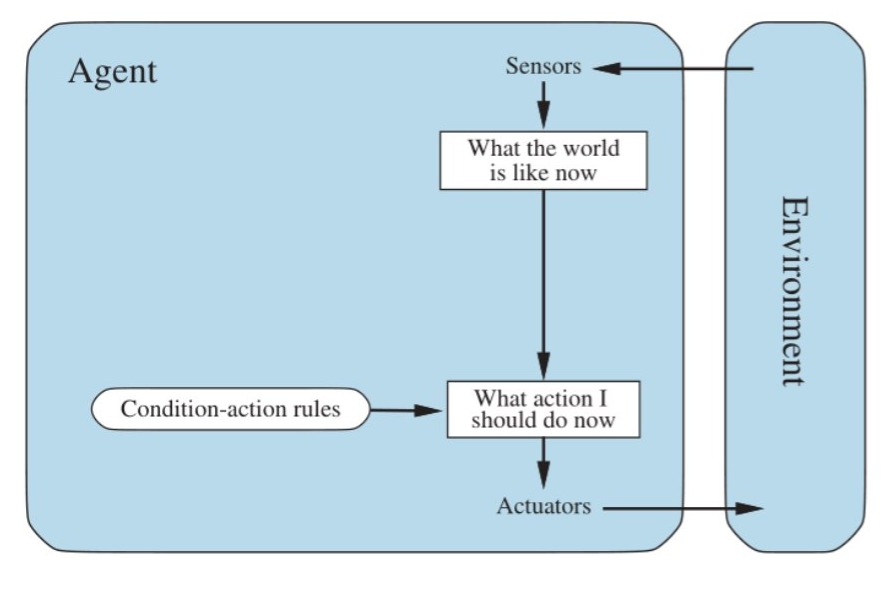

Simple reflex agents

Based only on current perception;

It works based on the if this then do that action rule

It will only work if the correct decision can be made based on present perception alone;

Fully observable environment;

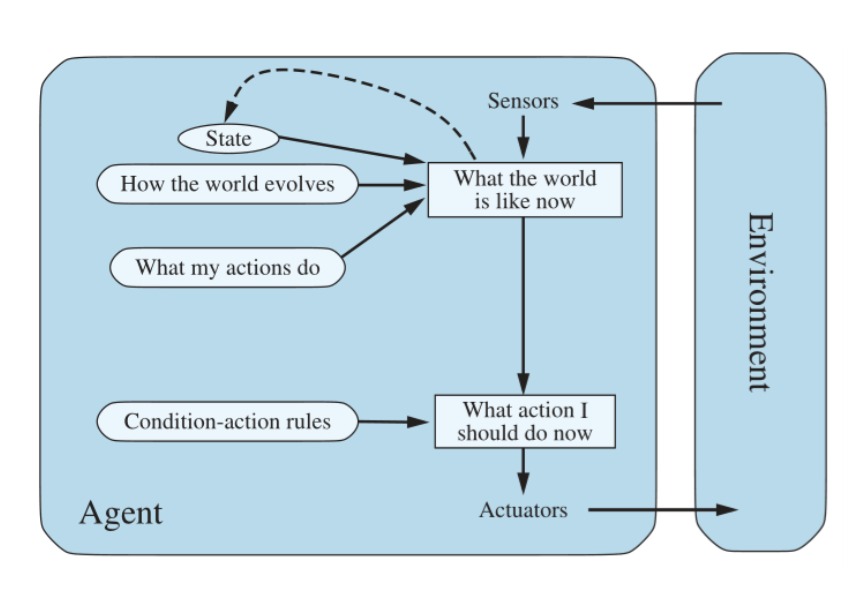

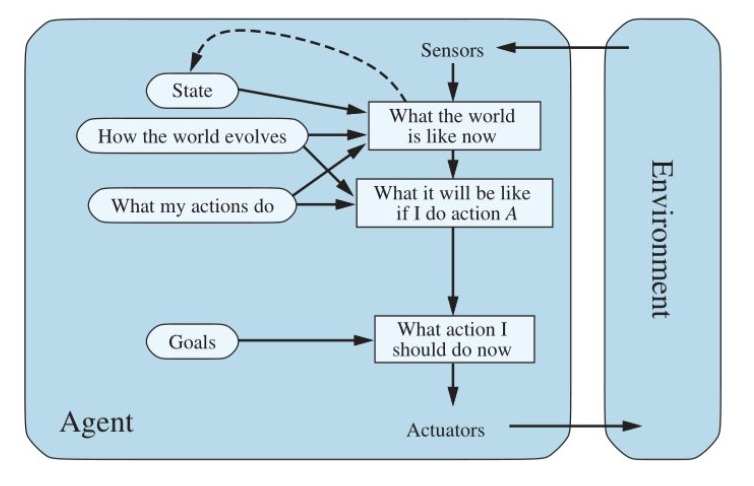

Model-based reflex agents

Partially observable environment;

Based on an internal state that holds some part of what is not currently being observed;

The internal state maintains some kind of history of perceptions;

Transient model describes how the environment changes with the agent’s action;

Sensory model describes the functioning and limitations of sensors;

Goal-based agents

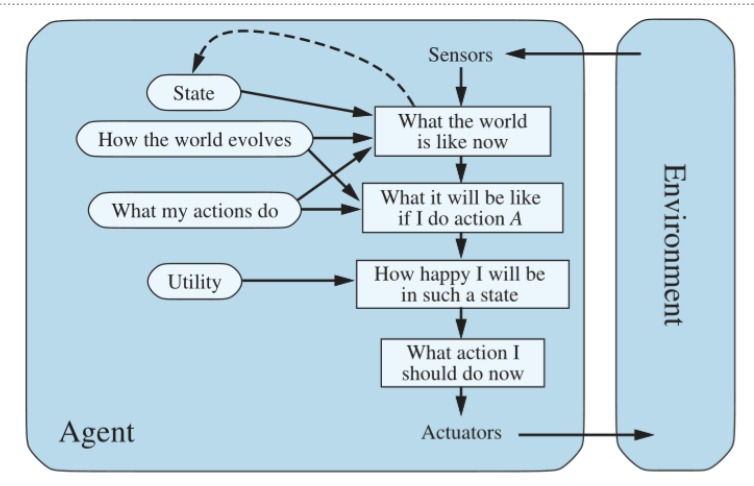

Utility-based agents

Objectives do not guarantee high quality or high performance;

Utility function (measures the agent’s performance);

Conflicting and competing objectives;

Probability of success vs. Importance;

Maximize expected utility;

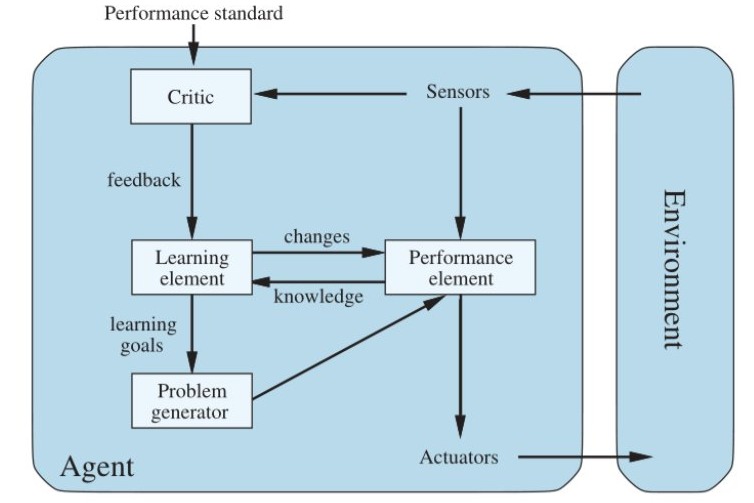

Agent Learning

Learning element: modifies the performance element based on the critical element;

Performance element: penalty vs. Award selects external actions;

Critical element: informs the learning element how well the agent is performing in relation to a fixed performance standard;

Problem generator: tests new possible solutions, even if known ones work;

Representation of states

Atomic representation: search, games, Hidden Markov Models, Markov Decision Processes, etc.

Factor representation: Constraint satisfaction algorithms, propositional logic, machine learning, Bayesian networks, etc.

Structured representation: Relational database, 1st order logic, 1st order probabilistic models, natural language, etc.

Problem Statement: Autonomous Crop Monitoring Drones

Description:

Agriculture plays a crucial role in global food production, and efficient crop management is essential for ensuring food security. To optimize crop monitoring, we propose the development of autonomous crop monitoring drones equipped with AI capabilities. These drones are tasked with assessing the health and growth of crops, enabling farmers to make data-driven decisions for improved yields.

P.E.A.S. (Performance, Environment, Actuators, Sensors):

Performance:

The performance measure for our autonomous crop monitoring drones is defined as the accuracy and efficiency of crop assessment, including early detection of disease, pest infestations, and growth patterns. It also considers the timely delivery of reports to farmers.

Environment:

The environment in which the drones operate is a dynamic, large-scale agricultural field. It is characterized by the following properties:

Partially Observable: The vastness of agricultural fields makes it impossible for drones to observe the entire field simultaneously. They must rely on sensors and data fusion to gain insights into crop health.

Multiagent: Multiple drones may operate in the same field concurrently, working collaboratively to monitor different sections.

Non-Deterministic: Crop conditions can change due to weather, disease outbreaks, or pest migrations, introducing uncertainty into the monitoring process.

Sequential: Crop growth is a continuous process, requiring regular monitoring and assessment over time.

Dynamic: The environment is subject to change due to factors like weather, irrigation, and farming practices.

Continuous: Crop assessment involves continuous data collection, making it a real-time, ongoing process.

Partially Known: While we have information about the field layout, crop types, and historical data, exact conditions can vary.

Discussion of Environment Properties:

Partially Observable: The vastness of agricultural fields necessitates that the drones operate with partial observability. They rely on onboard sensors, including cameras, infrared sensors, and multispectral imaging, to gather data about crop health. This property is essential as it mirrors real-world conditions where complete field visibility is unattainable.

Multiagent: In large fields, deploying multiple drones is practical to ensure comprehensive coverage. They may collaborate, sharing data and coordinating their monitoring efforts. Multiagent systems improve efficiency and reduce monitoring time.

Non-Deterministic: The dynamic nature of agriculture introduces non-determinism. Weather fluctuations, pest movements, and other unpredictable factors can impact crop health. Drones must adapt their monitoring strategies to address these uncertainties.

Sequential: Crop monitoring is an ongoing process. Crop growth and health change over time, and drones must assess these changes sequentially. This property ensures that timely actions can be taken, such as pest control or irrigation adjustments.

Dynamic: Agriculture is influenced by various dynamic factors, including weather patterns and farming practices. Drones need to account for these changes and provide insights to farmers for informed decision-making.

Continuous: Crop assessment involves real-time data collection. Drones continuously monitor crops, ensuring that data is up to date. This is vital for early detection of issues and prompt intervention.

Partially Known: While we have some knowledge about the field, such as its layout and crop types, the specific conditions within the field are subject to change. Drones adapt to the partially known environment by relying on historical data and real-time observations.

The development of autonomous crop monitoring drones with AI capabilities addresses the need for efficient and data-driven agriculture. By considering these environment properties, the drones can navigate the complex agricultural landscape, provide accurate assessments, and empower farmers with the insights they need for effective crop management.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the world of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is a dynamic and transformative realm that has evolved significantly over the years. From its historical roots in early AI concepts to its present-day applications, AI has grown to encompass a wide range of fields and technologies. The AI Index 2018-2019 showcases the substantial growth and impact of AI across the globe.

AI’s current capabilities, from robotics and autonomous systems to medical diagnostics and creative art generation, demonstrate its potential to improve various aspects of our lives. However, along with these opportunities come challenges and risks, including issues related to ethics, privacy, and bias.

Understanding the principles of rationality, task environments, and agent behaviors is essential for building effective AI systems that can operate in complex and dynamic settings. As AI continues to advance, its impact on society, industries, and decision-making processes is poised to be significant.

The journey of AI is marked by a constant quest for innovation and ethical considerations, with a balance between its remarkable potential and the need for responsible development and deployment.

References

- Professor’s slides and class material

- Open AI, GPT-3.5, Bing AI, Bard AI (Used to improve the structure of the text, correct grammar and syntax)